Preamble

The route of the Royal Saxon Way northwards from Tolsford Hill passes along the Elham Valley.

For the purposes of this note, the Elham Valley starts at Etchinghill and finishes at Bridge. Its stream is referred to here as The Nailbourne to comply with historic usage in texts and early maps. ”Nail Bourne” is used on 20th century Ordnance Survey maps with no apparent precedent. (See the separate note “The name of the Elham Valley stream” for a brief review of names which have been applied to this stream).

By most definitions, The Nailbourne is an example of a chalk stream with a characteristic mineral assemblage derived from water rising from the chalk aquifer. It is included in “Group A” in the Chalk-Stream Index compiled by Charles Rangeley-Wilson, that is, it rises from springs in the chalk, flows over chalk in contact with the chalk aquifer, and then flows over the younger sands and clays of the Tertiary cover. (The position of that geological boundary also coincides with the name change on current Ordnance Survey maps from Nail Bourne to Little Stour). However, The Nailbourne has become partially choked by alluvium in its upper reaches as the stream flow has reduced. This is likely to have altered its chemistry from that of a true chalk stream.

The geological sequence along The Elham Valley is simple. The rocks belong to the Chalk Group which dip slightly to the north east. Consequently, as you walk northwards along the valley, you pass over successively younger Chalk Formations. In fact, the route takes you over seven of the nine Formations which comprise all the Chalk sequence found in east Kent which dates from about 101 to 77 million years ago. The two youngest Formations, dating from about 77 to 66 million years ago, have been removed by erosion (or were never deposited here in the first place).

The high ground above the valley is mantled with Clay-with-flints, described previously in the Tolsford Hill section. The Sand in Clay-with flints is not here being confined to the high ground near the crest of the escarpment.

The lower slopes and parts of the base of the valley are mantled by a superficial deposit called Head, which is a catch-all term for any soil which has moved downslope from its origin. (However there are a few anomalous areas of Head mapped near the tops of the high ground between the valleys). Most of the deposits on the lower slopes probably date from the last ice melt. The downslope movement can result in an accumulation of Head along stream beds which are now dry, a useful device to identify the course of former streams where subsequent accumulation of sediment has caused the topography to become indistinct.

The youngest deposit, which is still being formed today, is “Alluvium”. This, by definition, is a sediment laid down by running water and so follows the bottom of the valley. Where Head is also present in the bottom of the valley, Alluvium usually overlies it.

If you have read this far then you are probably one of those people described in the Introduction who ask “Why is that valley shaped like that? How did it come to be there?” So, when you see the Elham Valley, you may well wonder how such a small stream could have eroded such a large valley. You will know that when you follow most rivers upstream, they diminish in size to a stream and eventually become a barely identifiable trickle of water. At the same time their valleys become shallow and indistinct, often disappearing altogether. This is not the case with valleys on each side of chalk escarpments. They are usually dry and the valley form remains recognisable for its entire length (see the section on Some origins of chalk downland landscape). But the Elham valley differs from most other chalk valleys, it widens out into a fan shape surrounded by hills with Tolsford Hill at its head. What is different about this valley?

The clues to one explanation are the two gaps (cols) in the head wall of the valley at Etchinghill and Postling. The North Downs escarpment was not always as high as it is now, it has been increasing in height since before the Ice Age. Rivers which flowed northwards down the slope of the Weald-Artois anticline were originally able to cut through the early escarpment, as the Great Stour does today. But not all rivers were large enough to keep pace with the uplift and were raised above the aquifer so that their valleys became dry. According to this idea, this is what happened to the two rivers which originally flowed through the Etchinghill and Postling gaps.

This is not the explanation which held during most of the last century which invoked melt-water floods, or high rainfall. See the section on A history of ideas on the origins of Chalk Downland landscape.

The Amble

As you start the descent from Tolsford Hill you can get a good view of the broad basin which forms the head of the valley. At the bottom of the hill, the route crosses the golf course to join Canterbury Road at Broad Street near the southern edge of Lyminge. From here, you can see bench-like lynchets, in the field known as Glebelands on the west side of Canterbury Road (Photo 1). These are listed in the KCC Heritage list as linear ridge features (Undated) (HER Number: TR 14 SE 236).

Lynchets are human-made terraces on sloping ground, often in the form of narrow field strips, but as is the case here, they can be wider features more like benches than strips. The lower bench curves around to join a small gully from which a spring issues below Rectory Lane. This form is similar to lynchets at Turleigh near Bradford-on-Avon. See the lidar image of those lynchets shown on the Bradford-on-Avon Museum web site, which are interpreted as a possible medieval field system.

The second terrace-like feature is upslope of the lynchet in Glebelands, at an elevation of about 110m and mentioned in KCC HER No: TR SE 236 (Photo 2). This feature is next to an old route into into Lyminge joining Rectory Road shown on early O.S. maps and so is likely to be associated with that route. At the southern end it becomes less distinct, but it can be followed eastwards crossing the road at Broad Street where it merges into a short but distinct increase in the road gradient.

There is similar feature upslope and to the west which is adjacent to a second old route into Lyminge leading to the cemetery.

The local geological memoir (Smart et al., 1966) reports the existence of river terraces along the Elham However, the memoir does also caution against mistaking lynchets for river terraces (see The 400ft Terrace).

There is a ditch on the west side of Canterbury Road where it enters Lyminge. It may at first sight give the appearance of a former road alignment or a perhaps a human-made drainage ditch, but the geological map shows a finger of “Head” running along its base confirming that it is a natural feature. Most Head deposits date from shortly after the last Ice Age (12,000 – 11,000 years ago). A nailbourne or winterbourne flows in this ditch when the water table is high (Photo 3).

Perhaps this ditch was the course of the original West Brook complimenting the current East Brook? Neither the name “Westbrook” or any stream appears here on maps produced in the last 300 years which gives an indication of the period of time since water was likely to have regularly flowed along this course.

The Head deposit following this ditch merges with a larger deposit which follows the course of the East Brook stream from Etchinghill into Lyminge and another which follows the stream issuing from the spring below Rectory Lane (See Photo 4). This configuration suggests that there was once a confluence of three streams at this location.

North of this junction the geological map shows an abrupt change from Head to Alluvium. This obviously does not indicate an abrupt change in the type of deposit but reflects a change in interpretation by The Survey, probably based on the age of the deposit, from an earlier deposit accumulated in a stream bed to a modern alluvial deposit. (It illustrates the sometimes arbitrary nature of the use of the names Head and Alluvium when it is difficult to decide where a stream bed deposit changes from old to modern).

Continuing north, the route passes through Lyminge, over the West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation at the base of the Grey Chalk Subgroup. It follows the East Brook and then The Nailbourne stream, remaining on the West Melbury Marly Chalk as far as North Lyminge. At this point the route crosses a fault boundary onto the overlying Zig Zag Chalk Formation, which underlies most of Lyminge including the church. This is the top part of the Grey Chalk. Although the Grey Chalk is not impermeable, its relative impermeability, compared with the overlying White Chalk, gives rise to springs, if not to the same extent as at the boundary between the Chalk and Gault clay.

The route continues to follow The Nailbourne northwards from Lyminge. As you approach Bereforstal Farm near Ottinge you pass by a mound between the path and the stream. This mound is shown on the 1888 – 1913, 6-inch O.S. Map series (Photo 5). The KCC Heritage List refers to this as spoil heap from a trial pit sunk in search of coal in the 19th century, HER No. TR 14 SE 44. The use of the term “trial pit” is probably an error. The coal deposits are a long way down below the Chalk, and certainly not within trial pitting depth. This, and the size of the mound, suggests that it is more likely to the spoil from a deep borehole. There is no record of a borehole here on the BGS GeoIndex so it does predate the formal recording of such excavations.

Continuing northwards, the RSW joins the lane called Lickpot Hill on the southern edge of Elham (TR 1782 4335, ///provide.cakewalk.bells). At this point the route passes onto the Holywell Nodular Chalk Formation. This is the base of the White Chalk Subgroup. The base of this Formation was last encountered at the top of Tolsford Hill. You can appreciate the effect of the north easterly dip of the Chalk (the slope angle of the strata) from this position by looking back along the valley to the top of Tolsford Hill (Photo 6). The O. S. maps show that the height difference between the base of the Holywell Nodular Chalk at Tolsford Hill and at Lickpot Hill is 95m and the horizontal distance is 5km. This equates to a dip angle of just over one degree – the usually reported dip of the Chalk here is one to two degrees.

As you enter Elham, there is another bench feature on the east side of the valley (Photo 7). The steep slope forming the edge of bench is unnaturally straight and well defined suggesting it is a man-made feature. (A solifluction movement would typically produce a lobed edge). There are small scale irregularities on the steep slope forming the edge of the bench which are like features which are caused by soil creep. These indicate that this face has existed for some time.

This feature is mapped within the New Pit Chalk Formation. The Geological Survey surveyors will have noticed this feature, but they have not interpreted it as a natural geological boundary. The digital geological map shows the boundary between the Clay-with-Flints and the underlying New Pit Chalk Formation to be further upslope, (marked by the hedge with isolated trees).

Early O.S. maps also show a field boundary following the top of this slope, indicating that is has some age (O.S. 25-inch map sheet LXVI.8, rev.1896). The steep slope which forms the edge of the bench is not marked by any boundary on the historic O. S. maps. There is no mention of a linear feature here on the KCC Heritage list.

Note that the bench curves around at its northern end to join the head of a small gully, although it looks as if there may have been some intervention, perhaps agricultural quarrying for chalk (Photo 8). But whatever, this configuration is like the bench noted in Photo 1, which was compared with the medieval Turleigh lynchets site. There is no current spring at this location but possibly water flowed from the gully in the past. Perhaps the proximity of a source of water influenced the choice of location of these terraces. The retention of water on slopes seems to be the purpose of terraces in use today.

Photo 7. Bench feature east of Elham (NGR TR 181 435, ///styled.heckler.curbed, viewed from RSW near Lickpot hill).

(NGR TR 1821 4340, //matchbox.winners.report)

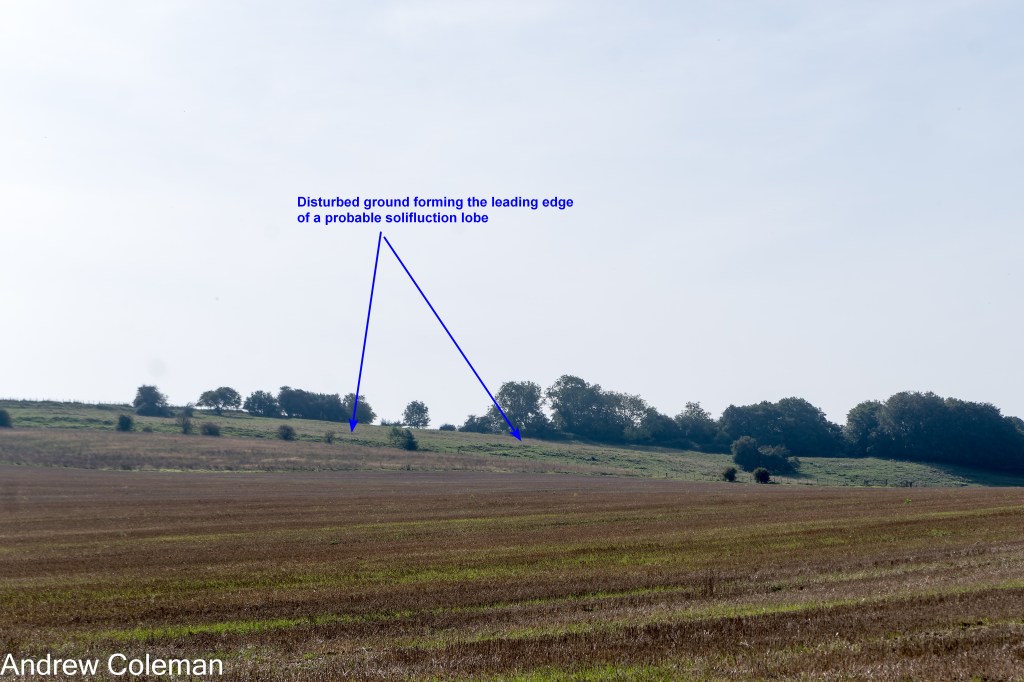

There are features on this slope further north along the valley, which are less marked but with a form more typical of solifluction lobes (Photo 9). These coincide with the edge of the mapped Clay-with-Flints outcrop which is a deposit which would be susceptible to solifluction.

A deviation: Follow this link to see an example of active solifluction lobes in north Kent.

Unless you “get your eye in”, there aren’t many landscape features which can be related to characteristics of the Chalk Formations along this section of the walk, so the geology may be difficult to relate to the landscape. But the sides of the valley around Elham do show a change in slope which relates to the underlying geology. The New Pit Chalk Formation, which overlies the Hollywell Nodular Chalk Formation, forms the lower, steepest part of the slope. The Lewes Nodular Chalk Formation underlies the top part of the slope and the boundary is marked by a reduction in gradient (Aldiss et al., 2012).

You can see an exposure of the New Pit Chalk Formation in the The Elham Chalk Pit, which has been excavated in the lower steep part of the valley, and shows its characteristic blocky structure. You have to take a short diversion along Duck Street from the square in Elham to find the pit. It is on the right hand side of the road just beyond the first bend (Photo 10). (The text on the information board, which dates from 1995, refers to “Middle Chalk” which is the old terminology used prior to 2005).

Continuing beyond Elham the route climbs the east side of the valley. Looking up along the slope, you can see a series of en-echelon, lens shaped benches in the upper slopes and there are corresponding but less well marked examples on the west side of the valley. Photos 11 and 12 give distant views taken from opposite sides of the valley where the en-echelon structure is easier to appreciate. Photo 13 is the close-up view taken from the RSW.

These forms are not typical of the examples of solifluction of the Clay-with-flints mentioned above, they are much larger and better defined than is typical of solifluction lobes. Their forms are more like those which can be produced by deep seated slope movements. If this what they are, they are likely to have involved mobilisation of frost shattered chalk. Their outcrop follows the slight northward dip of the chalk, and they are mirrored on the opposite side of the valley which suggests that their origin is related to a characteristic of the underlying geology. Their position coincides with the mapped boundary between the New Pit Chalk and Lewes Nodular Chalk formations. Without the benefit of an inspection trench, or expert opinion, the cause of these features remains uncertain.

Beyond Wingmore, the route alternately turns up and down the side of the valley, with no additional geological features of note. The path descends to Derringstone Hill south of Barham onto the Lewes Nodular Chalk on which it remains as far as Bridge.

The geological memoir (Smart et al., 1966) draws attention to river terraces on the sides of the valley between Barham and Kingston at an elevation of about 200ft AOD (60m). There are a couple of terraces at about the correct elevation which are more convincing than the reported 400ft terrace around Lyminge and which may be the terraces referred to. The RSW follows one on the east side of the valley which now accommodates The Grove (Photo 14). There is a matching feature on the west side of the valley formerly accommodating the Elham Valley Railway (O.S. 6 inch map sheet LVII.NW rev.1906) which has now been developed as housing along Heathfield Way. If these are river terraces, it is likely that both have benefited from some cut-and-fill works, to facilitate construction of housing, which has increased their definition.

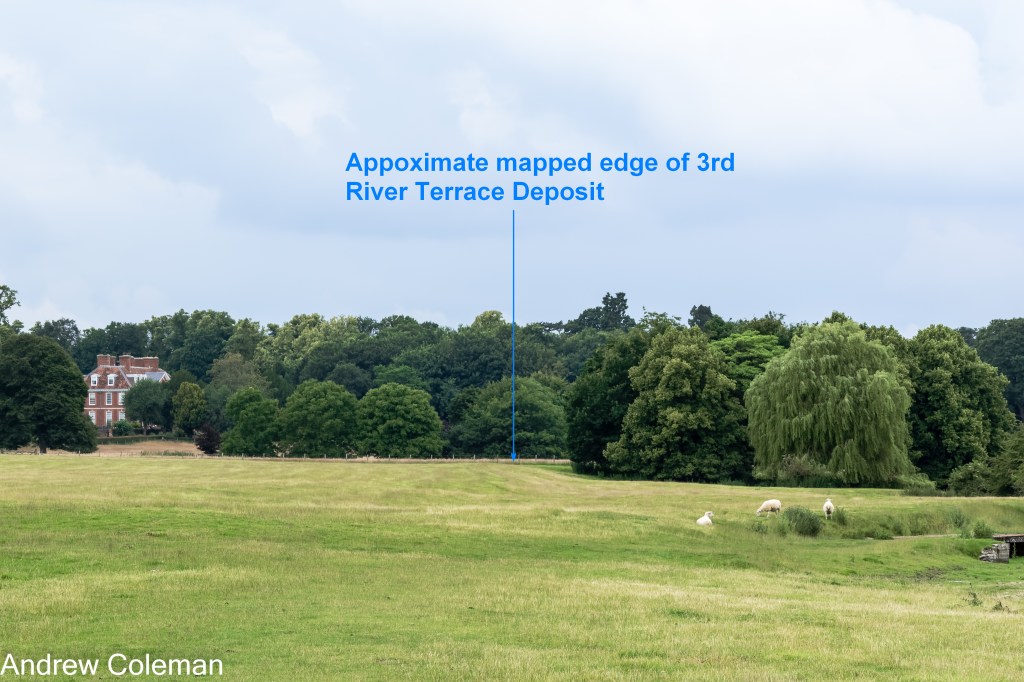

The direction of the valley turns through almost ninety degrees through Barham from northeast to northwest. At Bishopsbourne, the route beyond St Mary’s Church briefly follows a flood plain towards Bourne Park House, in the area labelled as “The Wilderness” on the 1:25,000 scale O.S. topographic map. The geological map shows the Third River Terrace Deposits on this plain and the topography shows at least two benches above the current (dry) stream bed (Photo 15). This is the first occurrence along the route of mapped River Terraces deposits, so there is little doubt that these features are river terraces.

The route finally leaves the Lewes Nodular Chalk as it climbs out of Bridge turning north east up on to the Seaford Chalk. Beyond this point the topography becomes less pronounced and this section is the subject of the section called “Bridge to Minster-in-Thanet”.

Andrew Coleman

Rev. 27/07/2025

References:

Aldiss, D. T., Farrant, A. R., & Hopson, P. M. (2012). Geological mapping of the Late Cretaceous Chalk Group of southern England: A specialised application of landform interpretation. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 123(5), 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2012.06.005

Farrant, A. R., & Aldiss, D. T. (2002). A geological model of the North Downs of Kent: the River Medway to the River Great Stour. www.thebgs.co.uk

Smart, J. G. O., Bisson, G., & Worssam, B. C. (1966). Geology of the Country around Canterbury and Folkestone. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.