There is an extensive tract of ancient landslips which affects the Lower Greensand Group (Atherfield Clay Formation to Folkestone Formation) in the Greensand escarpment between Aldington and Folkestone, a total distance of about 11 miles. You can often see evidence of fresh movement in wet winters on the slope at the “The Roughs” west of Hythe. You can also see the longer term effect of this landslip on a concrete Sound Mirror, a First World War aircraft early warning device (although this one dates from between the Wars).

The original slip probably dates from the “Big Thaw” at the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,000 to 12,000 years ago. The antiquity of this landslip is shown by the effect on Stutford Castle, a Roman Fort built on the landslip below Lympne. You can see the remains of some of its walls which have been dislocated by the landslip (see Photo. 1). This slope was clearly unstable in Roman times as remarked in the Geological Survey Memoir (Smart et al., 1966). This may be one of the few examples of Roman engineers getting it wrong. They seem not to have recognised the characteristic undulations indicative of unstable land-slipped ground but then, they didn’t have experience in reading the post glacial landscape of these northern climes.

This tract of landslips includes shallow slides, as at The Roughs, and deep-seated “rotational slips”.

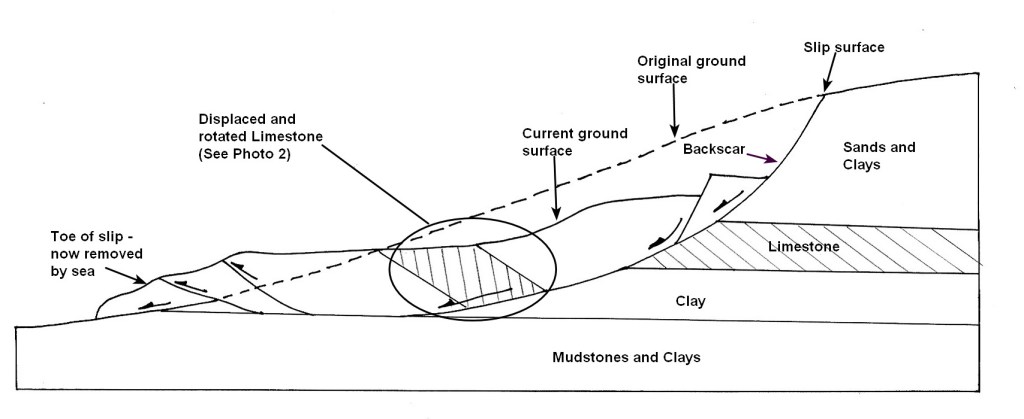

A rotational slip occurs along a slip surface which is concave down the slope and elongated along the slope. The top part of the slip surface may be near vertical, in which case after the slip has occurred, the remaining in-situ ground upslope may be visible as a “back-scar” cliff. The slip surface becomes less steep downslope as it follows the curved trajectory and eventually towards the toe of the slope it curves upwards, so here the angle of the slip surface is reversed.

This reversed slope is significant. The proportion of the slipped ground which is on the steep, upslope part of the slip surface reduces as it moves downslope over a surface with an ever-decreasing slope angle. This reduces the downslope sliding force (as happens when you approach the bottom of a playground slide). Meanwhile the ground which is accumulating at the toe of the slip increases the proportion of the slipped ground over the landward sloping part of the slip surface. This increases the upslope sliding force. Eventually the two opposing sliding forces balance each other, and the slip stops moving (see Fig. 1).

Large scale rotational slips comprise a succession of complex, over-lapping slip surfaces of different ages. The slip shown in Fig. 1 is oversimplified. Secondary slips occur in the slipped ground above the main slip surface. These often form during the main slipping episode but can occur at various intervals afterwards. The oldest, deepest slips can be recognised by the back-scar which is furthest up-slope. These are visible along the slopes above Hythe and Sandgate and can be recognised by their steep slopes, sometimes inland cliffs, and often by their curved outline when viewed on plan.

A slip surface, once formed, remains slippery and offers less resistance to ground movement along it than intact ground. Therefore, it only needs a relatively small out of balance force to reactivate an old slide. So, you can see that it is not a good idea to add weight to the top of a landslip or remove weight from the toe as this will upset the balance and is likely to reactivate the slide. But this does happen.

There were two large landslips in Sandgate in the 19th Century, in 1827 in east Sandgate and in 1893 in west Sandgate, both of which involved a reactivation of existing slip surfaces. Drainage was installed in the ground at the site of the 1827 slip in the mid-19th Century to increase the stability of the ground. The 1893 slip occurred immediately to the west of the 1827 slip and to the east of the (former) Military Hospital which also included ground drainage to stabilize the ground. The 1893 slip was described by Topley, (1893) and the following is a précis of his account: –

The slip was about 920 yds (841m) wide extending from the eastern end of the grounds of the old Encombe House and westwards towards the eastern end of the former Military Hospital. It stretched seaward about 233yds (213m) from the back of Encombe Grounds to the high-water mark which itself was moved about 100yds (91m) seaward. The greatest downward movement at the western part of Encombe Grounds was about 10 ft (3m), but at the eastern end of the grounds, where there were numerous small slips, the total movement may have been almost as great. Topley included the following observations in his account. These must have been made shortly after the slip had happened as evidenced by his observation of freshly slipped clay on the on the foreshore which wouldn’t have survived many high tides.

“The rainfall of February was unusually heavy.

“The slipped area is not drained, whereas the districts immediately to east (the 1827 slip) and west of it (the Military Hospital) are drained…….

“In consequence of extensive groyning to the west of Sandgate, the eastward travel of shingle was stopped and the seafront of Sandgate became almost bare of shingle…….

“The loss of shingle has no doubt rendered the land more insecure, there being less permanent weight on the foreshore.

“The recent slip commenced at about low spring tide on the evening of 4th March; the movement diminished as the tide rose …. and at low tide next morning a second slip took place.

“The band of clay opposite Gloucester Terrace and Wellington Terrace was forced up; the movement continuing during the Monday and perhaps later.”

(Topley 1893)

These observations describe the conditions necessary to reactivate an earlier landslip. High ground water levels caused by heavy rainfall, exacerbated by poor drainage, lead to a reduction of friction on the ancient slip surfaces reducing the frictional resistance to sliding. The loss of shingle on the beach removed weight from the toe of the landslip, reducing the upslope stabilising force. The account also describes the characteristic upward movement at the toe of the slip, indicative of a rotational slip, and the continued slow movements occurring over the following couple of days which are typical of slips in clayey soils. Minor slips and slow “creep” movements were occurring as recently as the 1990’s. Major civil engineering works to stabilise the slip were undertaken along the Sandgate seafront in the 1990’s.

Further descriptions of the landslip (and much else) are available in the Digital Archives of The Sandgate Society – https://sandgatesociety.com/archive-photographs/

If you were to take a deviation off the RSW and walk west along the Sandgate seafront, during a low water Spring Tide, you should see the toe of the ancient landslip described by Topley. This is a series of crescent shaped rock outcrops on the foreshore with strata showing a marked landward dip of about 40°, much more than their in-situ dip (Photo 2).

These rocks are Limestone, part of the Hythe Formation, which have been carried down the slope by land-slipping. They originate from an outcrop which was originally a seaward extension of the current outcrop in the slope behind the seafront, and several metres above ground level there. The rocks which you can see on the shore are equivalent to those circled on Fig. 1. They are at the seaward extremity of the slip and on that part of the slip surface which is tilting landward.

Andrew Coleman

Rev. 16/02/2025

References:

Smart, J. G. O., Bisson, G., & Worssam, B. C. (1966). Geology of the Country around Canterbury and Folkestone. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Topley, W. (1893). The landslip at Sandgate. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 13(2), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(93)80025-7