1 Introduction

Chalk Downland landscape in the UK is characterised by rounded grass covered hills and deep, steep-sided, dry valleys. It can be found from the Wiltshire Downs in the south to the Yorkshire Wolds in the north. The North Downs in east Kent include examples of these features in a compact and easily accessible area.

Chalk is a seabed deposit formed by an accumulation of shells from microscopic plankton which was compacted by the weight of accumulating sediments.

It is probably well known from school geography that parts of the Earth’s crust have been uplifted by deep seated, large scale, (tectonic) forces and then eroded to form hills and valleys. This has been the way landscape was formed throughout most of the Earth’s history. But it was only at the end of the last century that it was understood that the recent Ice Age climate played an important part in the formation of chalk downland landscape (reviewed in Gibbard & Lewin, 2003). Follow this link for A history of ideas on the origins of chalk downland landscape. In these notes, the term “Ice Age” is used do denote the Pleistocene glaciations, a succession of polar ice advances and retreats which started about 2.6 million years ago.

This note briefly reviews the role of tectonic uplift in the formation landscape in general, which is applicable to all rock types, then the main section deals with the effects of the Ice Age climate on the formation of chalk downland landscape. It is illustrated with local examples throughout.

2 The Role of Tectonic Uplift

2.1 The regional setting

The traditional ideas about how tectonic forces work assume that parts of the Earth’s crust have been compressed and uplifted to form mountains, while elsewhere crust extension caused thinning and sinking forming low-lying depositional basins covered by seas. (Chalk is a seabed deposit formed in one of those basins). This surface was then weathered and eroded to form hills and valleys.

The most recent compression event in southern England occurred when part of the Earth’s crust moved in a northerly direction pushing against the southern edge of an ancient stable block aligned east-west, passing through what is now southern England. But rather than causing flexing of the surface rock layers, the latest thinking invokes an upward movement along a series of ancient, almost vertical, deep-seated fractures in the ancient bedrock which produced an upward deflection in the overlying younger deposits. Eventually, this produced an elongated dome called The Weald-Artois Anticline, which stretches from east Hampshire to northern France (Jones, 1999b).

At the end of the last century Brodie & White, (1994), proposed an additional mechanism of uplift caused by magma accumulating beneath the crust causing the crust to bulge upwards. This is centred beneath Iceland (which is over the volcanically active Mid Atlantic Ridge) and so its effect is seen in the British Isles. They showed that of the degree of crustal compression required to produce uplift to the extent seen could not be produced by crustal compression alone. They also noted that the crustal compression was directed from the south, whereas the maximum uplift was in the north, closest to the Iceland magma bulge. Gale & Lovell, (2018) continued to develop this idea.

There appears to be agreement that there is disagreement about the number, timing and magnitude of these uplift events (Whiteman & Haggart, 2018) so the following is one, very much simplified, version of a timetable, but see Mortimore, (2019) for a detailed review.

The initial disturbances in the Earth’s crust affecting the chalk probably started at least as far back as the late Cretaceous Period about 70 million years ago, towards the end of the formation of the chalk (R. Mortimore & Pomerol, 1997) This continued in pulses, with an accelerated phase at the end of the Paleocene and beginning of the Eocene (56 million years ago) – according to the Magma bulging idea and/or at the end of the Paleogene and beginning of Neogene (about 23 million years ago) according the crustal compression idea and again at the beginning of the Pleistocene (Jones, 1999b) (2.6 million years ago at the beginning of the Ice Age).

Whatever the timing, at some stage, uplift was accompanied by the erosion of about 350m of Chalk and younger rocks over the higher part of the Weald-Artois anticline. Continuing uplift eroded the top of the Weald-Artois Anticline leaving the North and South Downs on its flanks.

In the context of the development chalk downland landscape, it is important to note that an uplift phase occurred at the start of the Ice Age, estimates vary but a rise of 200m is commonly quoted. This last phase of Ice Age uplift was amplified locally by an upward tilt of the southern England and a corresponding downward movement in the north caused by the weight of the ice sheet in the north summarised in Jones, (1999a).

2.2 The effects of uplift on drainage in south east Kent.

At an early stage, before the Weald-Artois Anticline became prominent, the upward movement of the deep-seated ancient rocks caused the overlying younger rocks to flex upwards slightly over the east-west axis and to tilt north and south each side of this axis. Initially, the top of the anticline was probably eroded at a similar rate to the uplift, so the effect on topography would have been minimal, but erosion did expose a succession of strata at the surface aligned in a roughly east-west direction. These strata had differing susceptibilities to erosion, so rivers flowed preferentially along the weaker rocks forming an east-west drainage pattern (Jones 1999b and Murton J. B. & Giles D. P., 2016). As the anticline developed, a new drainage regime developed in which rivers flowed north and south down each side in response to the increasing gradients.

In the local area, the North Downs began to present a barrier to the northward flowing rivers as uplift progressed. A few larger rivers were sufficiently well established to continue cutting down through the emerging escarpment, the Great Stour is the local example. But continuing uplift caused most of the valleys running across the North Downs to become dry as they rose above the water table. Jones, (1999b) considers that the final uplift event occurred at the beginning of the Pleistocene (i.e. Ice Age) and it was this uplift which initiated in the development of the escarpments.

The interruption of northward flow across the escarpment caused the rivers to the south of the escarpment to reverse their direction southward into the East Stour catchment. New north and south flowing river systems developed on each side of the escarpment. Continuing uplift and increasing elevation above the water table caused the springs on the dip slope to move further down the valleys following the point of interception with the water table. This progression is recorded in historical records.

2.3 The cols at Etchinghill and Postling – examples of features caused by uplift.

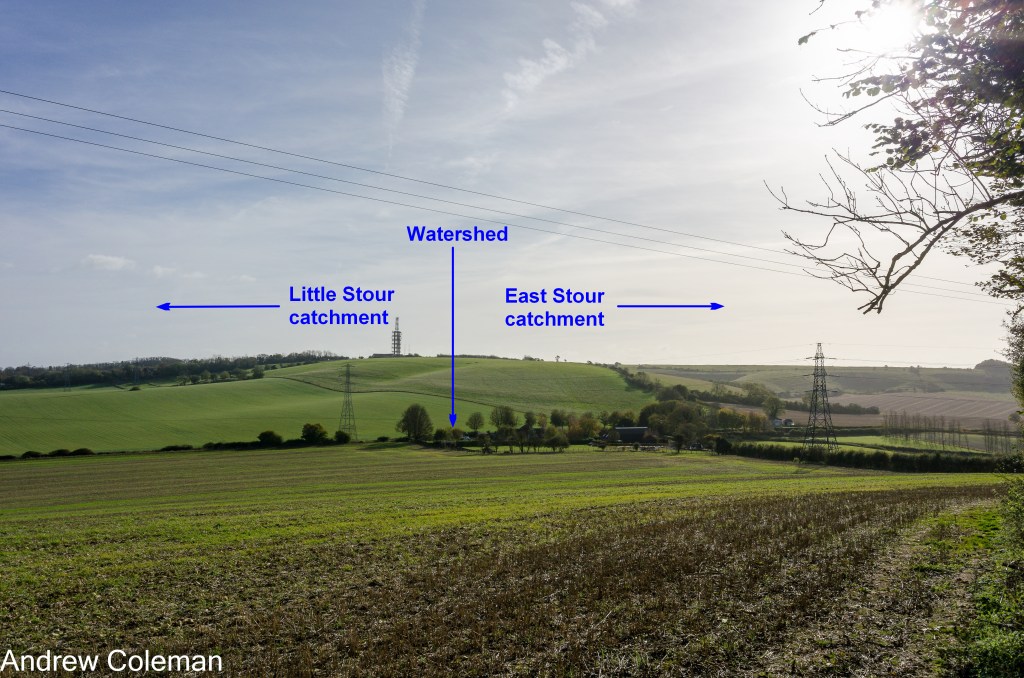

The cols at Etchinghill (elevation 110m – 115m AOD) and above Postling (elevation 122m AOD) may be the remains of two of those smaller valleys which were left high and dry over the crest of the rising escarpment. The location of the original rivers are likely to have been influenced by a pair of geological faults which pass through the escarpment here. Many chalk rivers follow fault lines which have weakened the chalk encouraging preferential erosion along them. The cols now mark the watersheds between the Little Stour drainage catchment to the north and East Stour catchment to the south.

Water still flows northward down the Elham Valley from the Etchinghill col arising from the spring in the village. These springs issue from the interface between the White Chalk and the Grey Chalk which whilst not impermeable is relatively impermeable compared to the White Chalk.

Springs also issue from the base of the scarp slope, and feed south into the Seabrook Stream. These springs issue from the interface between the Grey Chalk and the impermeable Gault and form the main spring line at the base of the Chalk Group. These springs have cut back into the scarp slope here and the resulting topography has made the watershed between the Little Stour and the East

Stour catchments obvious.

The Postling col is now dry. There is a lobe of Head deposits extending south from the head of the Elham Valley into the col. This may indicate the course of the original river which flowed north through the col. The springs which issue from the scarp slope below the Postling col are some distance to the south of the watershed, in the village of Postling. There has been no over-steepening of the scarp slope close to this watershed which makes it less obvious than the one in the Etchinghill col. The opposing gradients are visible when viewed from above Staple Farm (Photo 1).

But whatever the origin of these cols, the topography at the head of the Elham Valley is most easily explained if this was the location of the confluence of two rivers which flowed through the escarpment before significant uplift.

3 The Role of the Ice Age climate

3.1 Regional Setting

After the end of the Cretaceous Period (about 66 million years ago), the climate began a global cooling trend from the “Hothouse” climate of the Cretaceous through Sub-Tropical to Warm Temperate. This was assisted locally by a northward drift of that part of the Earth’s crust now occupied by the British Isles by about 12° of latitude from its origin (refs. cited in Gibbard & Lewin 2003). If you travelled 12° south from the North Downs at Dover you would come to the latitude of Ibiza.

There was a marked fall in temperature at the beginning of the Pleistocene, about 2.6 million years ago, which heralded a period of unstable climate during which ice sheets in the northern hemisphere alternately advanced (glaciations) and retreated (interglacials) from around the North Pole.

The glacial-interglacial cycles were characterised by gradual fall in temperature leading into the glacial phase and a quicker rise in temperature at the end. Until about 900,000 years ago, the length of these cycles was about 41,000 years. Since that time, the length of the glacial cycles has increased, to 100,000 years, and the magnitude of the temperature change within each cycle has also increased. The periodicity now approximates to an 80,000-year glacial and a 20,000-year interglacial (Rose, 2010).

This periodicity has been shown to correspond to Milankovitch cycles which are changes in the amount of heat reaching the Earth from the Sun caused by predictable variations in the Earth’s orbit. (For further details see the section on Milankovitch Cycles in “Determining a timetable of glaciations”). These variations are small, but they have the greatest effect at high latitudes where radiation from the Sun is weak.

The ice sheets did not extend as far south as the North Downs but during the glaciations the climate was cold here, similar to tundra regions today, with permafrost extending to depths of up to 20 – 50 metres below the surface (Murton J. B. & Giles D. P., 2016). Permafrost refers to ground in which the temperature remains at or below freezing point for more than two years, whether or not it contains any water to form ice.

As noted earlier, the current thinking is that it was climate, rather than tectonic uplift, which was the instigator of erosion of the chalk downs during the Pleistocene and particularly the thaws at the end of the glaciations (Gibbard & Lewin, 2003). The sections below describe how the peculiar processes operating during the Ice Age tundra climate altered the chalk landscape.

But before proceeding it is worth noting that in terms of landscape formation, not a lot has happened since the last glacial thaw about 11,000 to 12,000 years ago which is very recent in geological time. The landscape we see around us today is essentially a landscape formed in a tundra climate. It has been little altered since by the agents of weathering and erosion operating in the current temperate climate. The development of temperate climate vegetation has produced the greatest change in appearance, but this superficial, the underlying tundra landforms remain. The freshness of the chalk landscape may be more convincing if the conversion from geological to human timescale is used, which imagines that the oldest rocks date from the time of Stonehenge, as outlined in the Introduction in “Dealing with geological time”. Conversion to this timescale would place the beginning of the Ice Age at 40 days ago and the last thaw at 4 or 5 days ago.

3.2. The effect of the Ice Age climate on the weathering of rocks.

The higher temperatures existing prior to the Ice Age had promoted chemical weathering of rocks. This is an aggressive form of weathering which operates most effectively in tropical and equatorial regions today. It reduces rocks to fine grained debris (clays, silts, and sands – using the ground engineering definition) to great depths and leaves a thick fine-grained weathered layer overlying a chemically weathered surface etched into the bedrock. The depth to this surface can reach 30m in current tropical soils.

In those warmer times, rivers were like equatorial rivers today, they were large and meandered across a heavily forested landscape. They were able to remove the fine-grained weathering residue and so kept pace with the relatively slow opposing uplift. Whilst the rivers were meandering elsewhere, dense forest stabilised the low-lying land. The key result was that these large rivers maintained a low relief landscape (Gibbard & Lewin, 2003). It was also under these conditions (according to a currently favoured idea) that much of the chalk, about 350m covering the emerging Weald-Artois Anticline, was removed.

With the onset of the Ice Age the new low temperatures were below the levels needed to support chemical weathering. It was replaced by mechanical weathering which at this time was primarily the freeze-thaw action of ice. This form of weathering does not break down rocks to the same degree, or to the same depth, as chemical weathering and it produces much coarser debris (sands, gravels and cobbles – using the ground engineering definition). Erosion was now unable to keep pace with uplift which, according to some accounts, had increased at this time. The result was a more pronounced relief.

3. 3 The effects of permafrost

3.3.1 Permafrost and meltwater floods

The Victorian geologist, Clement Reid, noted that permafrost would make the Chalk behave as an impermeable rock (Reid, C. 1887). He also recognised the Chalk’s susceptibility to disintegration by freeze-thaw weathering, allowing it to be more easily eroded. These two properties of frozen Chalk, its impermeability and its fragility, lead Reid to suggest that ‘violent and transitory mountain torrents….would tear up a layer of rubble previously loosened by frost….’ (Reid, C. 1887) and that this was responsible for the erosion of deep, steep sided valleys in the permeable Chalk. See the separate section on A history of ideas on the origins of Chalk Downland Landscape for contex.

3.3.2. Permafrost and mass movement

Mass movement refers to movement of soil and rock downslope by gravity as distinct from sediment moved by water or wind (“soil” here, meaning that which isn’t rock or organic material). In the context of the Chalk, when frost shattered permafrosted chalk thaws, the mixing of meltwater and ice with the fine-grained chalk debris makes it behave as a viscous fluid, that is, it can flow downslope very slowly. This is solifluction, or strictly gelifluction, because ice is involved. The mass keeps moving as long as the water remains at the critical level. It stops moving as the water drains away.

This distinction between solifluction and gelifluction isn’t just semantics, the mechanisms differ in one crucial respect. In a geliflucting mass, the supply of water is renewed as the included ice melts and so the mass keeps moving for longer and further than would a soliflucting mass supplied only by its initial charge of water.

Where there is snow cover, meltwater trickles out from beneath the melting snow, removing chalk in suspension and solution (referred to as nivation).

The conditions most conducive to all these processes would be one where the temperature is constantly around freezing, so that freezing and thawing were happening simultaneously in different parts of the mass.

These mechanisms are responsible for the shape of the short, steep sided valleys in the Chalk, known as coombes, which are seen in the scarp slope and the heads of some of the dip slope valleys. This type of mass movement removes chalk from the head slopes of the valleys, as much as from the sides of the valleys, which explains the characteristic steep slopes at the ends of coombes, which are difficult to explain in terms of stream erosion (Osborne White, 1924). On reaching the valley floor, the semi-liquid mass moved slowly along the coombe eventually solidifying in front of it in the form of a fan, a characteristic feature found in front of these coombes.

Some of the coombes east of the Etchinghill col are more “V” shaped and have streams issuing from the spring line on top of the Gault clay. These are examples where water has played a part in the final stages of their formation. It is difficult to envisage a situation where a coombe could be formed entirely by mass movement without any stream erosion. It seems likely that stream flow would have at least eroded an initial gully and then taken over again at each thaw.

These mechanisms only operate on a weak porous rock in a tundra climate. There’s currently nowhere in the tundra where you can see these mechanisms operating (all the weak rocks have been removed by ice sheets in the polar regions) so the validity of these explanations cannot be checked by observation. But no-one has yet come up with an alternative way of explaining the unique form of these coombes; the steep head slopes and flat bottoms cannot be explained solely by the action of water as pointed out by Reid (1887).

The idea that meltwater floods were responsible for these deep dry valleys was still current in recent times. (You can still see an old explanation board on the North Downs Way at TR 1427 3962 ///forgiven.dignify.mammoth, attributing glacial meltwater as the cause of the nearby coombe).

3.4 Summary

It seems likely that all the above mechanisms played a part in shaping the Ice Age Chalk Downland Landscape. More prominent were those associated with snow melt – mechanical weathering, nivation, solifluction – but also normal erosion by streams and rivers including spring sapping and stream capture.

4 Examples of landscape features resulting from the Ice Age climate

4.1. River Terraces

Tectonic uplift plays a part in the formation of these terraces, but it seems to be agreed that the mobilisation of water required to produce them was initiated by climate induced periods of alternating freezing controlling melt water flow (Bridgland, 2006) There was a stage during the interglacial periods when rivers cut down into the valley floors and, in the well-established downstream parts of the valley, they left parts of the old floors along the sides of the valleys as terraces. Successive down-cutting left a series of terraces down the sides of the valleys. Many of these terraces are still covered by the original sediments left by the rivers, which are referred to as River Terrace Deposits. The oldest terraces are found at the highest levels and the youngest are found closest to the current valley floor.

In southeast England the terraces are confusingly numbered 5th to 2nd – oldest to youngest. Bridgland (2006) dated the oldest river terraces in the lower Thames Valley to about 478,000 years ago (his findings are valid beyond that valley). The youngest date from the last Ice melt dating from about 12,000 to 11,000 years ago. Bridgland correlated the dates of these terraces with the 100,000 year, Milankovitch Cycles (roughly 20,000 year interglacials and 80,000 year glacials), thus linking the river terraces to the glaciation cycles. This placed the origin of the Chalk Downland river valleys in the Ice Age.

(There are two interpretations of the timing of the down-cutting phases which differ in detail. The traditional interpretation described in the local Memoir (Smart, et al., 1966), correlates the down cutting phase with the melt water floods at the end of the glaciations. A more recent interpretation by Bridgland (2006) places the down cutting phase during the temperate interglacial phase, at least in the downstream parts of valleys, which removed an accumulation of sediment which had occurred during the glacial phase when freeze-thaw erosion was at its height).

4.2. The origin of the Channel.

Possibly the most dramatic change in chalk landscape was the formation of The Channel (Strait of Dover). The Chalk cliffs at Dover and those at Cap Blanc-Nez, on the opposite side of The Channel, are both part of a chalk escarpment which originally continued across the channel along the north side of the Weald-Artois anticline, called the Weald-Artois ridge. This section describes how part of the Weald-Artois ridge was removed leading to the formation of The Channel. (This ridge is often called the “land-bridge”, but this is confusing as there has been more than one land-bridge across the North Sea over time. Archaeologists use this term when referring to the most recent one, Doggerland, – see the end of this section below. So here, land-bridge is used as a generic term and Weald-Artois ridge and Doggerland are used as names of specific features.)

Before the removal of the Weald-Artois ridge, the Atlantic coastline extended east as a deep bay probably as far as the mouths of the Rivers Somme and Solent, both of which drained into the Atlantic. On the northeast side of the ridge, the pre-cursors of the main river systems of northern Europe, The Rhine, Meuse and Thames drained into the North Sea and onwards to the North Atlantic.

During the Ice Age glaciations, which started about 2.6 million years ago, Ice sheets covered much of the land in the northern hemisphere, but it wasn’t until about 478,000 years ago, at the start of the Elsterian (Anglian) Glaciation that the British and Scandinavian ice sheets combined for the first time. This formed a barrier across the northern end of the North Sea preventing drainage to the North Atlantic. The Weald-Artois ridge was blocking its southern end so, with no outflow possible, the North Sea became a lake supplied by meltwater and flow from the precursors of those north European rivers. The water level of the lake rose to the level of the lowest part of the Weald-Artois ridge which controlled the water level in the lake. You can see these lake sediments in the coastal cliffs of Norfolk and they show that the water level in the lake rose to about 30m above current sea level.

It has been accepted for some time that the Weald-Artois ridge was breached by overtopping of the North Sea Lake, about 450,000 years ago during the Elsterian Glaciation (Gupta et al., 2007), but whether the breach was by gradual erosion, or a sudden event was not clear.

The early ground investigations, carried for the construction of the Channel Tunnel, identified several deep sediment filled depressions which were termed “Fosse Dangeard”. Their origin was uncertain. They were initially thought to buried valleys formed by glacial erosion until it was found that the ice sheets never reached this far south, but there was also speculation that they were plunge pools formed beneath waterfalls flowing from the North Sea lake. Following further geophysical investigations over the succeeding years, each producing higher resolution results, it became clear from their location relative to the Weald-Artois ridge, their internal profile and their great depth, that they could only have been plunge pools eroded beneath huge waterfalls (Gupta et al., 2017).

Seven major plunge pools were identified with depths ranging from 50m to 140m and many smaller ones with depths of less than 20m. They are spread in a line parallel and adjacent to the Weald-Artois ridge over distance of 7km. They are also in groups orientated at right angles to the chalk ridge and each plunge pool is elongated suggesting that the waterfalls were cutting back north east into the Weald-Artois ridge and towards the North Sea lake. The waterfalls are conservatively estimated to have been 60m – 70m high. So, it appears that ridge was breached by a 7km wide cataract.

Once the land-bridge was breached, marine erosion quickly removed any chalk sea-stacks remaining between the breaches and the North Sea was connected to the Channel.

A 80km long 10km wide channel, The Lobourg Channel, was also revealed in the early investigations which is orientated along The Dover Strait. It has an almost box-like cross section with straight sides and cuts through obstacles such as hard strata without deviation or change of form. The only obstructions which remain are in the form of streamlined “islands” along the base of the valley.

This type of geometric valley profile was first noted in the “Channeled Scablands”, of north western Washington State, in the 1920’s. Its origin was attributed to erosion by a high volume, high velocity flood, in this case caused by the breaching of a very large ice-dammed lake (Lake Missoula). Estimates of the speed of flow of the Lake Missoula flood waters range up to 80mph (130kph). The recognition of a feature in the Dover Strait which was the same as the Missoula flood channel was convincing evidence for a mega flood here, and likely to be associated with the breaching of the Weald-Artois ridge.

The Lobourg Channel continued to be eroded long after the initial breach. It cuts through the plunge pools therefore it post-dates them. There is an inner, and therefore more recent, channel within the main Lobourg Channel which shows the straight, steep sides with streamlined “islands” typical of those formed by the Lake Missoula mega flood. So, there has been more than one mega flood in the channel in addition to that following the initial breach. It probably dates from the Wolstonian / Saalian glaciation about 160,000 years ago.

Doggerland.

The term “land-bridge” is often used in the context of migration of flora and fauna to and from the mainland during the Ice Age but it is not always clear what is being referred to. There has been at least one, occasion when it was possible to cross by land from Europe to the British Isles since the breach of the Weald-Artois ridge and possibly three. During each glacial period, sea levels in the North Sea dropped, exposing land as water was locked up in the ice sheets. There have been three such glacial periods since the breach of the Weald-Artois ridge

During the most recent glaciation (the Devensian) the North Sea dried out, or was at best marshland with tidal creeks. This was “Doggerland”. The glacial maximum, and hence the lowest sea levels, lasted from about 27,000 to 12,000 BCE. During this time large river systems draining northern Europe and southern Britain coalesced in The Channel to the north east of the Straights of Dover and flowed southwest. The size of these rivers would have deterred crossing using the short route between the current locations of Calais and Dover, but it would have been possible to cross to the north of these rivers, between the Netherlands and East Anglia.

Archaeological evidence shows that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers took advantage of fish from tidal creeks, and of the influx of prey animals over the newly exposed land and established settlements on Doggerland. As is the case today in the Tundra, large animals moved north in Summer towards the ice margin to take advantage of the spring vegetation.

Doggerland was last flooded by rising sea level in about 6,200 BCE, and is likely to have been hastened by a tsunami flood caused by a large landslide on the Norwegian coast.

4.3. The Devil’s Kneading Trough coombe.

The Devil’s Kneading Trough coombe is in the scarp slope of the downs above the village of Brook (Photo 2). It has unusually regular sides, even by coombe standards, and its head is double ended giving it a fish tail shape. It looks man-made, and to some extent it is. In a review of studies of sediments in the coombe, Kerney et al., (1964) noted the presence of artefacts from the Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages. They suggested that evidence of soil disturbance was caused by Iron Age ploughing adjacent to the tops and along the base of the coombe and this could have enhanced the abrupt changes of slope.

They noted that the remains of flora and fauna in the sediments of the valley bottom were predominantly land based, albeit marshy, with very few representatives from streams, indicating that processes other than flowing water were involved in the formation of the coombe. (Reid, (1887) had come to a similar conclusion in the coombes of the South Downs – see A history of ideas on the origins of Chalk Downland landscape). They suggested that solifluction must have played a part in transporting the chalk debris away from the coombe, but they considered that transport by meltwater from snowfields was of equal if not greater importance as shown by the bedding and rolled chalk gravel (not noted by Reid in the South Downs).

Kerney et al., (1964) found by dating the sediments eroded from the coombe and deposited in front of it, that most of it dated from a 500-year period between 8,800 and 8,300 BCE comprising what they called Zone III deposits. This was revised by later analysis to 9,700 BCE. for completion of the erosion phase.

They also estimated that about one third of the total volume of chalk eroded is within a radius of less than a mile from the coombe (Kerney et al., 1964, p185). As they also stated that most of this comprises their Zone III deposit, this implies that a volume equivalent to at least half of the volume previously removed was eroded during the last erosion phase.

Kearney et al. attributed the rapid erosion to a humid climate with temperature hovering around freezing which was conducive to mass movement of frost shattered chalk. This example shows that it is the alternate freezing and thawing of chalk, rather than a constant frozen condition, which breaks the chalk down to a material which is susceptible to mass movement by solifluction or gelifluction. It also shows how quickly this type of erosion can remove large volumes of chalk.

4.4. Cirque-like coombes.

There are three bowl-shaped hollows in the north facing dip slope of the escarpment in the Postling col (Photo 3). In hard rock mountain areas, similar features are called “Cirques” or “Corries” and are attributed to an erosional process called “nivation”. This is a type of erosion which occurs beneath an accumulation of ice or snow, when meltwater flows along the interface between ice and the underlying rock. This flow erodes the rock beneath the patches of snow or ice which develop over time become more pronounced and encourage the retention of more snow.

During the last stages of the ice melt on the Downs near Postling, the northerly aspect would have been favourable for the maintenance of residual snow patches. Diurnal, or at least seasonal, freeze-thawing produced meltwater flowing beneath the snow patches and enlarged the hollows producing the cirque-like coombes shown in Photo 3. These are at high level, well above the spring line at the base of the scarp slope and likely to have always been above the water table in the dip slope, so spring-fed streams were unlikely to have been involved in their formation.

4.5. Asymmetric Valleys.

Many of those tributary dry valleys of the Elham Valley which are orientated roughly east-west show asymmetry of their slopes. The northerly facing slopes are steeper than the southerly facing slopes. This is a feature typical of a landscape formed in cold climates and is a result of their aspect, where nivation is prevalent on the cold north facing slopes. In that respect they are like the north facing coombes described above.

The Skeete Valley, west of Lyminge, is a good example of slope asymmetry (Photo 4) as is the Loughborough Lane Valley to the south. Kerney et al., (1964) noted that of the six coombes which they studied along the scarp slope east of Brook, the three which are closest to an east-west orientation have north-facing slopes which are steeper than those opposite. However, in coombes in the Chilterns the steeper slopes are found on the west and south facing slopes. Kerney et. Al., (1964) suggest that in those cases the daily temperature variation on these sunny slopes is responsible for their asymmetry.

There is an example of two adjacent valleys which appear to have been caused by uplift in one case and the Ice Age climate in the other. Follow this link to An odd alignment of valleys.

Andrew Coleman

Rev. 09/02/2026

References:

Bridgland, D. R. (2006). The Middle and Upper Pleistocene sequence in the Lower Thames: a record of Milankovitch climatic fluctuation and early human occupation of southern Britain. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 117(3), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(06)80036-2

Brodie, J., & White, N. (1994). Sedimentary basin inversion caused by igneous underplating: Northwest European continental shelf. Geology, 22(2), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1994)022<0147:SBICBI>2.3.CO;2

Gale, A. S., & Lovell, B. (2018). The Cretaceous–Paleogene unconformity in England: Uplift and erosion related to the Iceland mantle plume. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 129(3), 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2017.04.002

Gibbard, P. L., & Lewin, & J. (2003). The history of the major rivers of southern Britain during the Tertiary. In Journal of the Geological Society (Vol. 160). http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/

Gupta, S., Collier, J. S., Palmer-Felgate, A., & Potter, G. (2007). Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel. Nature, 448(7151), 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06018

Jones, D. K. C. (a). (1999a). Evolving Models of the Tertiary evolutionary geomorphology of southern England, with special reference to the Chalklands. In Ulift Erosion and Stability: Perspectives on Long-term Landscape development. (Vol. 162, pp. 1–23). Geological Society, London Special Publications.

Jones, D. K. C. (b). (1999b). On the uplift and denudation of the Weald (B. J. Smith, W. B. Whalley, & P. A. Warke, Eds.; SP 162, pp. 25–43). Geological Society. http://sp.lyellcollection.org/

Kerney, M. P., Brown, E. H., & Chandler, T. J. (1964). The Late-Glacial and Post-Glacial History of the Chalk Escarpment near Brook, Kent. Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society of London., 248(745), 135–204.

Mortimore, R. N. (2019). Late Cretaceous to Miocene and Quaternary deformation history of the Chalk: Channels, slumps, faults, folds and glacitectonics. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 130(1), 27–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2018.01.004

Mortimore, R., & Pomerol, B. (1997). Upper Cretaceous tectonic phases and end Cretaceous inversion in the Chalk of the Anglo-Paris Basin. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 108(3), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(97)80031-4

Murton J. B., & Giles D. P. (2016). The Quaternary Periglaciation of Kent. Field Guide. Quaternary Research Association.

Reid, C. (1887). On the origin of Dry Chalk Valleys and of Coombe Rock. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 43, 364–373.

White, H. J. O. (1924). The geology of the country near Brighton & Worthing.

Whiteman, C. A., & Haggart, B. A. (2018). Chalk Landforms of Southern England and Quaternary Landscape Development. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2018.05.002