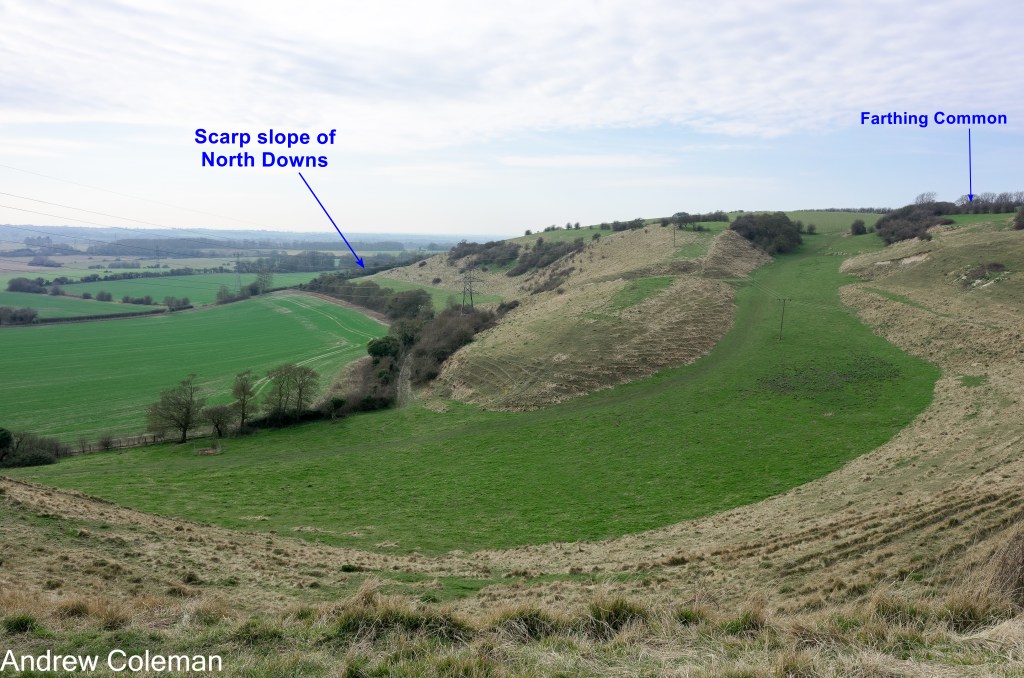

There is an oddly aligned dry valley northwest of Postling. It runs down eastwards parallel to the crest of the escarpment into the Postling col where it makes a right-angled turn to the south (See photo 1). The oddity here is that the original stream did not take the more direct route from its origin, down the adjacent scarp slope rather than running parallel to it for a considerable distance (about a kilometre).

As well as its odd alignment, this valley is shallower with more gentle slopes than is usual for those valleys which are close to the Chalk escarpment. Those valleys are normally shaped like coombes, they are deep, with steep sides and a flat bottom. Their origin is attributed to the effects of melting permafrost and solifluction. The shape of this shallow valley is more typical of one formed by flowing water.

British Geological Survey digital maps Geoindex and BGS Geology Viewer (viewed 2025) show Alluvium along the base of this valley which suggests that at one time it contained flowing water. The printed map, published 1966 (re-print 1990) also shows Alluvium, although maps from Digimap Geology show Head along the bottom of this valley. Head is usually mapped in the bottom of coombes, presumably to reflect its non – fluvial origin. The Survey seems to use the terms Head and Alluvium interchangeably, apparently naming old Alluvium as Head – see the abrupt mapped boundary between the two deposits shown in the East Brook valley on the southern side of Lyminge – NGR TR 16357 40755.

One explanation of the odd alignment may be found in the scenario outlined in “Some origins of Chalk Downland landscape” section 2.2, “The effects of uplift on drainage in south east Kent.” That describes how early rivers flowed down the northern side of the developing Weald-Artois anticline and locally across what was to become the North Downs escarpment before it had risen sufficiently to present an obstacle. Some continued flow northward, eroding through the rising escarpment, keeping pace with uplift, and continue today (The Stour and Medway rivers for example). Others failed and their valleys remain as dry cols in the crest of the escarpment (the Etchinghill and Postling cols).

These early rivers were joined by tributaries flowing down the sides of their valleys, following the same alignment as the shallow valley. If this valley was formed by one of those early tributaries, perhaps the reason that its stream did not flow down the adjacent scarp slope is that the scarp was not there, or if it was it was poorly defined.

The Geological Survey Memoir for Canterbury and Folkestone “The Memoir” (Smart et al., 1966) includes an alternative explanation the origin of the shallow valley. It assumes that the escarpment existed but it does not address the oddity of why the river did not flow down the adjacent scarp slope. But it does explain the right-angled bend at the bottom of the valley.

It suggests that the original shallow valley stream was an eastward flowing headwater of the Elham Valley stream (now called The Nailbourne) which was flowing north from the col. There was also a stream arising from a spring at the foot of the escarpment on the south side of the col which flowed south into the East Stour catchment. The spring cut back northwards into the scarp slope. It eventually intercepted the Nailbourne and diverted its headwaters southwards, cutting off the supply to the Nailbourne downstreamFollow this link to Examples of stream capture?

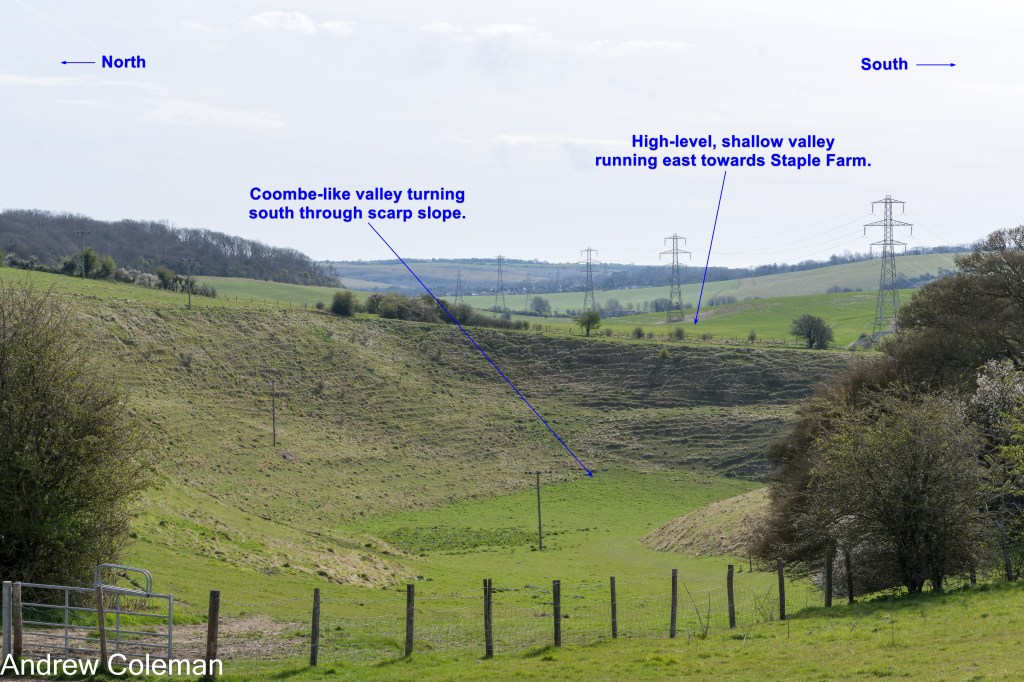

There is a second valley near Postling and immediately to the west of the head of the shallow valley referred to above which has the form of a typical coombe. The top part of that valley follows the line of the shallow valley to the east but then turns abruptly south, cutting through the adjacent scarp slope, as might be expected (Photos 2 – 4). So, when this coombe was formed, the scarp slope was present and sufficiently developed to influence the direction of the stream. This would imply that this coombe is much younger than the shallow valley to the east.

N.B. The marked difference in the colour of the grass between the base and the sides of this valley is only apparent in early spring. This reflects the difference between the underlying chalk and solifluction deposit (“Head”).

down the shallow valley shown in Photo 1 (viewed from NGR TR 1389 3987, ///atoms.kiosk.whimpered).

Given the proximity of this coombe to the well-researched Devil’s Kneading Trough, 5 miles to the west (Some origins of Chalk Downland, Section 4.3) it is likely to share a similar history, i.e., it is a recent feature, much of it formed during the end of the last glaciation and ice melt.

The British Geological Survey digital maps (Geoindex and BGS Geology Viewer) show the base of this valley and the Devil’s Kneading Trough to be underlain by “Head”. In these previously glacial tundra environments, Head usually refers to material which is derived from mass flow deposits produced by thawing of permafrost chalk. Photo 5 shows brecciated chalk and weathered, probably in-situ, chalk exposed in a slump scar in the side of the upper part of the coombe.

It seems likely that the alignment of the scarp slop coombes is affected not only by the proximity of the slope, but also by the existence of discontinuities in the chalk (joints and faults). It is a well-known feature of waterflow in chalk that pathways preferentially develop and along existing joints which then become more permeable as water flow continues to widen the joints (this characteristic is used by water engineers to “develop” water wells in chalk).

There is a coombe on the south slope of Tolsford Hill which also changes direction through 90° (Photo 1, Royal Saxon Way, Tolsford Hill). This coombe partially follows the alignment of a fault shown on the BGS Geoindex map trending approximately North West to South East. The Etchinghill and Postling cols both follow the lines of mapped faults.

There are no faults mapped in the coombe near Postling but the chalk is blocky (the Zig-Zag Chalk Formation) and so is likely to be jointed. Middlemiss, (1983) reported two major joint sets in east Kent, one orientated at 300° and another at 205° – 210° which is a similar alignment to the faults in the cols.

The gully shown in Photo 6 could be an early phase in the development of a coombe. Its “V” shape suggests that erosion by water was significant factor in its formation. It would seem likely that coombes were initiated by streams during one of the interglacial periods by streams following the line of discontinuities. They were subsequently enlarged by solifluction but their course was established by the initial streams which were in turn influenced by the orientation of the discontinuities in the chalk

In summary, the coombe near Postling and the shallow valley next to it are likely to have been formed by different processes at different times. Confirmation of the nature and age of the sediments in the base of both valleys would go a long way to resolving uncertainty surrounding their histories. Perhaps, it is pertinent to note that in their review (Whiteman & Haggart, 2018) remark that given the length of time involved (from the late Cretaceous through to the Quaternary), it would be surprising if the origin of chalk landscape features were not the result of more than one process. These two valleys appear to demonstrate this diversity.

Andrew Coleman

12/01/2026

References:

Middlemiss, F. A. (1983). Instability of Chalk cliffs between the South Foreland and Kingsdown, Kent, in relation to geological structure. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 94(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7878(83)80003-0

Smart, J. G. O., Bisson, G., & Worssam, B. C. (1966). Geology of the Country around Canterbury and Folkestone. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Whiteman, C. A., & Haggart, B. A. (2018). Chalk Landforms of Southern England and Quaternary Landscape Development. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2018.05.002